This post focuses on our Native American heritage who resided along the borders of the Chesapeake Bay. Digressing just a little into my lineage, my paternal Bolling ancestors were among the first in Jamestown and my maternal Lathrop ancestors the first in New England. My ninth great-grandfather, Colonel Robert Bolling married Pocahontas’ granddaughter, Jane Poythress Rolfe, daughter of Thomas Powhatan Rolfe (the only child of Pocahontas [daughter of Powhatan and Chief of the Algonquian Nation] and John Rolfe) and his wife, Jane Poythress.

I am a native born Southern Marylander (the state named after the English Queen Henrietta Maria [1609-1669], wife of Charles I of England, and daughter of Henry IV of France).

I descend primarily from European emigrants (Great Britain [67%], Ireland [10%], and Western Europe [7%]), who helped found Jamestown, Virginia in 1607–America’s first permanent English Colony. So, coming from Maryland and having ancient aristocratic ancestors who helped form the Commonwealth of Virginia (two states that border the Chesapeake Bay) as well as Native American heritage I always have had a natural curiosity about the origin of the Chesapeake, its name, and inhabitants along its borders.

The Chesapeake Bay At A Glance

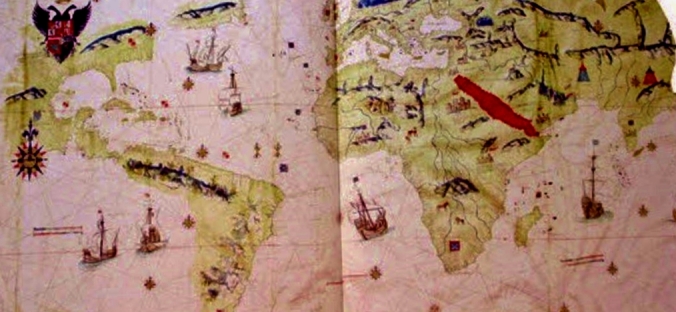

Pictured below is the earliest map to show the existence of the Chesapeake Bay, called “Baya de Santa Maria.” Juan Vespucci was the royal pilot of Spain’s hydrographic office and nephew of Amerigo Vespucci, after whom North and South America are named. The information on this map came from a 1525 voyage by Pedro de Quexos.

Because the Chesapeake Bay has been so important to the history of Maryland, charts have played a central role from the 17th Century forward.

From the Maryland State Archives website, I gleaned the following key points about the Chesapeake:

- In North America, the Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary, a semi-enclosed coastal body of water with a free connection to the open sea.

- Some 35 million years ago, a bolide, an object similar to a comet or asteroid, struck the present-day Delmarva Peninsula, creating a 55-mile-wide crater. The depression created by the crater changed the course of rivers and determined the location of the Chesapeake Bay.

- The Bay, as we know it today, was created about 10,000 years ago when melting glaciers flooded the Susquehanna River Valley.

- Today, fresh water from land drainage measurably dilutes seawater within the Bay. For ocean-going ships, the Bay is navigable with two outlets to the Atlantic Ocean: north through the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal in Cecil County, and south through the mouth of the Bay between the Virginia capes.

- Native Americans living along its shores gave the Bay an Algonquian name. Chesepiook, meaning “great shell-fish bay,” was used to signify the abundance of Bay crabs, oysters, and clams.

- In June 1608, Captain John Smith led two voyages throughout the Chesapeake Bay, and in its midst European settlers first landed at St. Clement’s Island, Maryland, in 1634.

- Through the lower portion of the Bay, pirates settled and attacked ships off the coast. And, at its southernmost reaches during the Civil War, the first ironclads, the Confederate Merrimac and the Union’s Monitor, fought to a draw near Hampton Roads, Virginia, in March 1862.

- Many shipwrecks, remains of vessels sunk by natural forces, human error, or attack, lie deep under the Chesapeake Bay.

Native American Ancestors before the Europeans Arrived

Estimates vary, but according to the National Park Service’s Chesapeake Bay Office which coordinates partnerships to develop and sustain national historic trails, it is likely that 50,000 or more people called the Chesapeake region home before the English arrived. Their ancestors had lived here for 40,000 generations—at least 10,000 years—so the ways of life of the native people were highly adapted to the geographic environment. Their economic, cultural, social, political, and spiritual systems were well established and sophisticated.

The First People of the Chesapeake

Chesepians were the Native American inhabitants of the area now known as South Hampton Roads in Virginia during the Woodland Period (1000 BCE to 1000 CE), and later prior to the arrival of the English settlers in 1607. They occupied an area which is now the Norfolk, Portsmouth, Chesapeake and Virginia Beach areas. They were divided into five provinces or kingdoms: Weapemiooc, Chawanook, Secotan, Pomouic and Newsiooc, each ruled by a king or chief. To their west were the members of the Nansemond tribe.

The main village of the Chesepians was called Skicoak, in the present independent city of Norfolk. The Chesepians also had two other towns (or villages), Apasus and Chesepioc, both near the Chesapeake Bay in what is now Virginia Beach. Of these, it is known that Chesepioc was located in the present Great Neck area. Archaeologists and other persons have found numerous Native American artifacts, such as arrowheads, stone axes, pottery, beads, and skeletons in Great Neck Point.

Politically, the area was dominated by the Virginia Peninsula-based Powhatan Confederacy. Although the Chesepians belonged to the same eastern-Algonquian speaking linguistic group as members of the Powhatan Confederacy across Hampton Roads, the archaeological evidence suggests that the original Chesepians belonged to another group, the Carolina Algonquian. Powhatan, whose real name was Wahunsunacock, was the most powerful chieftain in the Chesapeake Bay area, dominating more than 30 Algonquin-speaking tribes. The Chesepians did not belong to Powhatan’s alliance but instead defied him.

As English writer, William Strachey (1572-1621) documents in his book The Sea Venture, the “Chesapeake People” were murdered before our European ancestors arrived.

History books tell us that in 1609 Strachey, on the ship Sea Venture, headed to Virginia looking for adventure. A hurricane caused the Sea Venture to run aground at Bermuda. In The Sea Venture, he writes of his ten-month long struggle for survival. (William Shakespeare used Strachey’s The Sea Venture book as the basis for his play The Tempest.)

The castaways, while marooned on Bermuda, built boats from their wreckage and eventually made it to Virginia and Strachey then began documenting life in the new colony. Because of his fascination with the Native American inhabitants, he also compiled a dictionary of Algonquin language. (The only other known record of Algonquin words was made by John Smith.)

In talking with the natives Strachey discovered information about them that few Europeans had learned. The Indians told him about the remarkable Chesapeake tribe.

He learned that a few years before the arrival of Europeans, the Algonquin priests informed Chief Powhatan that a great danger would arise from the shores of the Chesapeake Bay– so dire that it would destroy their empire, civilization, and ways of life. They told him his Confederacy of 30 tribes would be gone, their villages burned, and all of his people dead.

The Algonquin priests repeatedly pressed Powhatan to take action against this small peaceful tribe of 300-400 Chesapeakes who lived near the mouth of the Bay. At first, Powhatan resisted because his priests could not give him specifics. Unfortunately for the Chesapeake Indians, Powhatan’s priests’ visions were persistent and became more compelling. And, sometime around 1606, the Powhatans murdered the entire Chesapeake tribe.

On returning to England in 1611 Strachey published his book, The Historie of Travaile Into Virginia Britannia where he described the stories he heard from the Powhatans about their destruction of the Chesapeake (Chessiopeians) tribe:

“...not long since that his priests told him how that from the Cheaspeack Bay a nation should arise which should dissolve and give end to his empire, for which, not many yeares since (perplext with this divelish oracle, an divers understanding thereof), according to the ancyent and gentile customs, he destroyed and put to sword all such who might lye under any doubtful construccion of the said prophesie, as all the inhabitants, the wereoance and his subjects of the province, and so remaine all of the Chessiopeians at this daye, and for this cause, extinct. ”

During the 1970s and ’80s, archaeologists discovered the remains of 64 Chesapeake Indians during development in the Great Neck area of Virginia Beach. Those bones dated to between 800 B.C. and A.D. 1600. In April 1997, after decades of trying to recover these Native American remains, the Nansemonds’ reburied them near the English’s First Landing site in Virginia.

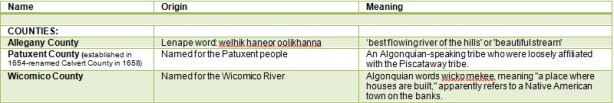

And yet today, we still can see evidence of our Native American roots in our counties and place names along the Chesapeake regions. We live in Calvert County that originally was established as Patuxent County in 1654 (named after the Patuxent people) and note that its name was changed to Calvert County after Lord Calvert of Baltimore in 1658. Just down the road from us a piece is Chesapeake Beach, named for the Chesapeake people who were an Algonquian-speaking tribe who resided in Virginia. And fortunately for us, there are many more words and names that remain as they were known centuries ago.

About Algonquian-speaking Tribes

In the tables below, you will see references to “Algonquian-speaking tribes.” The word Algonquian (or Algonkian) is a general linguistic/anthropological term used to refer to not only the small Algonquin tribe but dozens of distinct Native American tribes who speak languages that are related to each other.

Native American County Names

Native American Villages, Towns, and Cities Names

From www.ethnologue.com (the comprehensive reference site that catalogs all the known living languages [7,106] in the world today), I discovered the various tribes that made up the Algonquian-speaking confederacy and are included in the Algic Family language classification system–one of the largest indigenous language families of North America. It consists of 44 languages, the overwhelming majority of which (42 languages) belong to the Algonquian branch. The bulleted list below shows the Algonquian-speaking tribes and their countries of origin (Canada or the United States). I have highlighted in green below the 12 Eastern Algonquian-speaking tribes who resided in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia along the Chesapeake Bay borders:

- – Algonquian (40)

- Blackfoot [bla] (A language of Canada)

- Cheyenne [chy] (A language of United States)

- Menominee [mez] (A language of United States)

- Miami [mia] (A language of United States)

- Shawnee [sjw] (A language of United States)

- – Arapaho (2)

- Arapaho [arp] (A language of United States)

- Gros Ventre [ats] (A language of United States)

- – Cree-Montagnais (9)

- Atikamekw [atj] (A language of Canada)

- Cree, Moose [crm] (A language of Canada)

- Cree, Northern East [crl] (A language of Canada)

- Cree, Plains [crk] (A language of Canada)

- Cree, Southern East [crj] (A language of Canada)

- Cree, Swampy [csw] (A language of Canada)

- Cree, Woods [cwd] (A language of Canada)

- Montagnais [moe] (A language of Canada)

- Naskapi [nsk] (A language of Canada)

- – Eastern Algonquian (12)

- Malecite-Passamaquoddy [pqm] (A language of Canada)

- Micmac [mic] (A language of Canada)

- Mohegan-Pequot [xpq] (A language of United States)

- Narragansett [xnt] (A language of United States)

- Powhatan [pim] (A language of United States)

- Wampanoag [wam] (A language of United States)

- – Abenaki (2)

- Abenaki, Eastern [aaq] (A language of United States)

- Abenaki, Western [abe] (A language of Canada)

- – Delaware (2)

- Munsee [umu] (A language of Canada)

- Unami [unm] (A language of United States)

- – Nanticoke-Conoy (2)

- Nanticoke [nnt] (A language of United States)

- Piscataway [psy] (A language of United States)

- – Fox (2)

- Kickapoo [kic] (A language of United States)

- Meskwaki [sac] (A language of United States)

- – Ojibwa-Potawatomi (9)

- Algonquin [alq] (A language of Canada)

- Chippewa [ciw] (A language of United States)

- Ojibwa, Central [ojc] (A language of Canada)

- Ojibwa, Eastern [ojg] (A language of Canada)

- Ojibwa, Northwestern [ojb] (A language of Canada)

- Ojibwa, Severn [ojs] (A language of Canada)

- Ojibwa, Western [ojw] (A language of Canada)

- Ottawa [otw] (A language of Canada)

- Potawatomi [pot] (A language of United States)

- – Unclassified (1)

- Lumbee [lmz] (A language of United States)

- Wiyot [wiy] (A language of United States)

- Yurok [yur] (A language of United States)

Many Algonquian languages are extremely endangered today. Only a handful of them has a significant number of speakers. Of the original 42 Algic languages, only about 27 of them are used today. The largest group is Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi with 104,000 speakers, while the largest single language is Ojibwa with some 35,000 speakers. Ten languages are already extinct, and many are on the verge of extinction. Most surviving languages are spoken by older adults who are not passing their language on to their children.

Below the double lines, I included a more complete Chesapeake Bay History Timeline that spans (according to the scientists) 35 Million Years!

A Chesapeake Bay History Timeline as Created by Chesapeakebay.net

- 35 Million Years Ago – A rare bolide (a comet- or asteroid-like object) hits what is now the lower tip of the Delmarva Peninsula, creating a 55-mile-wide crater. This crater influences the shape of the region’s rivers and determines the eventual location of the Chesapeake Bay. As sea levels fluctuate over the next several million years, the area that is now the Bay alternates between dry land and shallow coastal sea.

- 18,000 Years Ago – Glacial sheets from the most recent Ice Age begin to retreat. The region’s climate begins to warm. (Image courtesy Twelvex/Flickr)

- 15,000 BC – As the climate continues to warm, a landscape that was once dominated by conifers begins to change. Oak, maple, hickory and other hardwood species appear. (Image courtesy Nicolas T/Flickr)

- 11,500 BC – Paleo-Indian people arrive in the region. Over the next thousand years, the climate becomes increasingly humid and the landscape gives way to hardwood forests and coastal wetlands. Paleo-Indians modify their hunting technology accordingly, replacing Clovis points with spear-throwing devices that can be launched over expansive terrain. (Image courtesy Ficusdesk/Flickr)

- 10 to 2 Million Years Ago – Chi Poon/Wikimedia Commons A series of ice ages locks ocean water in massive glaciers. The mid-Atlantic coastline extends 180 miles farther than its current location. In warmer periods, a glacier melts into the headwaters of the Susquehanna River, carving a valley through Pennsylvania and pushing sediment into the Coastal Plain. In colder periods, conifer forests attract deer, bears, and birds to the region.

- 10,000-7,000 BC – Ice sheets and glaciers continue to melt, flooding the Susquehanna, Potomac, James and York rivers. Water pours into the Atlantic Ocean and sea levels rise. The Chesapeake Bay’s outline begins to form. Mammoths, giant beavers and other Ice Age creatures are now extinct. (Image courtesy Dru!/Flickr)

- 5,000 BC – Temperatures continue to rise. A mixed deciduous forest dominates the landscape. Acorns and other nuts become a key food source. Diverse fish and shellfish populations are abundant in the region’s rivers. The first oysters colonize the Bay.

- 2,000 Years Ago – The Chesapeake Bay’s outline now resembles its current form. Native American populations continue to develop more sophisticated hunting methods, including the bow and arrow. The Bay’s waters are dominated by oysters, clams and fish, like bass and shad. Shellfish becomes an increasingly important food source. (Image courtesy AerialOutline/Flickr)

- 1,000 Years Ago – Native Americans clear forests to create farmland. A reliance on agricultural crops like corn, squash, beans and tobacco leads to the creation of more permanent town villages. (Image courtesy brandoncripps/Flickr)

- 1500 – The Native American population reaches 24,000.

- 1524 – Italian Captain Giovanni da Verrazano is the first recorded European to enter the Chesapeake Bay. (Image courtesy F. Allegrini/Flickr)

- 1561 – While exploring tidewater Virginia, Spanish conquistadors capture a young Native American. They name him Don Luis and bring back to Spain, where he receives a formal education. (Image courtesy barxtux/Flickr)

- 1570 – Don Luis returns to the Chesapeake region as a guide and interpreter with the St. Mary’s Mission, a small group of Spanish Jesuits seeking to establish a religious camp. Don Luis quickly abandons the group and returns to his people. Months later, he leads a massacre against the St. Mary’s Mission, killing all but a young servant boy.

- 1607 – An expedition funded by The Virginia Company of London arrives in the Chesapeake Bay. They establish the first permanent English settlement in North America in Jamestown, Virginia. (Image courtesy Jay I. Kislak Foundation )

- 1608 – Captain John Smith sets off on the first of his two voyages around the Chesapeake Bay. In his journal, he records detailed descriptions of his surroundings. In the years to follow, he draws an elaborate and remarkably accurate map of the Bay and its rivers. (Image courtesy National Park Service)

- 1650s – The tobacco industry is booming in the lower Chesapeake colonies. Colonists clear land for agriculture and use hook-and-line to catch fish in the Bay’s shallow waters. War and disease take their toll on Native Americans, whose population shrinks to 2,400—just 10 percent of the size it was when Europeans first arrived in the region. (Image courtesy Trevor Haldenby/Flickr)

- 1680s – Virginia lawmakers pass legislation to prevent wasteful fishing practices on the Rappahannock River. Colonists begin using hand tongs to harvest oysters. (Image courtesy Steve and Sara/Flickr)

- 1700s – English settlements grow rapidly as agriculture expands. The first signs of environmental degradation occur. A patchwork of rural farming and fishing communities develops on the western and eastern shores of the Chesapeake Bay. (Image courtesy Claude Moore Colonial Farm)

- 1750s – Colonists strip 20 to 30 percent of the region’s forests for settlements. As a result, shipping ports begin to fill with eroded sediment, becoming too shallow for boats to navigate. Commercial fishing for species like shad and herring begins. (Image courtesy SoilScience)

- 1770s – The colonial population exceeds 700,000. Farmers begin to use plows extensively, starting a cycle of permanent tillage that prevents reforestation and leads to massive soil erosion. (Image courtesy American Art Museum/Flickr)

- 1781 – After eight years of fighting, the Revolutionary War ends when British Lord Charles Cornwallis surrenders at Yorktown, Virginia. The former British colonies are on the verge of forming a new, unified nation. The Chesapeake Bay region will come to serve as a key economic and political center. (Image courtesy John Trumbull/Wikimedia Commons)

- 1785 – Virginia and Maryland sign the Mount Vernon Compact, also known as the Compact of 1785. Virginia agrees to give vessels bound for Maryland free passage at the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay. In return, Maryland gives citizens of both states the right to fish in the Potomac River. (Image courtesy NCinDC/Flickr)

- 1820s – Railroads, canals and steamboats offer new transportation options, benefiting the coal, steel and oyster industries. (Image courtesy JRiver/Flickr)

- 1829 – The 14-mile Chesapeake and Delaware Canal is built, linking the Chesapeake Bay with Delaware Bay and opening undeveloped land to agriculture and the harvest of timber. (Image courtesy Anthony Bley/Wikimedia Commons)

- 1840s – Half of the region’s forests have been cleared for agriculture, timber and fuel. The first imported fertilizers are used after ships bring bird guano from Caribbean rookeries and nitrate deposits from the Chilean coast. (Image courtesy calwest/Flickr)

- 1850s – Railroads, canals and steamboats have allowed the oyster market to reach consumers outside of the Chesapeake region. The number of oysters harvested from the Bay has doubled in the last 10 years, from 700,000 bushels in 1839 to more than 1.5 million in the 1850s. (Image courtesy swamibu/Flickr)

- 1860s – Water supply systems are constructed to transport drinking water to Baltimore and the District of Columbia. Sewer systems are built to send waste and runoff into the rivers that flow into the Chesapeake Bay. Brick, stone, iron and steel replace wood as the region’s source of heat, light and building material. (Image courtesy Wayan Vota/Flickr)

- 1880s – Wooden skipjacks—or vessels that are adapted to sail on Chesapeake Bay waters—are built in response to increased demand for oysters. Twenty million bushels of oysters are harvested from the Bay each year. (Image courtesy University of Delaware Library/Flickr)

- 1890s – Sixty to 80 percent of the forests along the Baltimore-Washington corridor have been cleared for agriculture and development. Coal-burning industries spew smoke into the air and send pollutants into the region’s rivers. The construction of highways links cities and suburbs. (Image courtesy Nick Humphries/Flickr)

- 1900s – The replacement of railroad ties removes an estimated 15 to 20 million acres of eastern forests. A dramatic drop in oyster populations starts to affect Chesapeake Bay health, and state and federal laws move to control the industry. Scientists begin question the impact of human behavior on the Bay. (Image courtesy accent on ecelectic/Flickr)

- 1920s – Swamps and marshes are drained to create room for waste dumps and new development. The Conowingo Hydroelectric Generating Station, also known as the Conowingo Dam, is built at the mouth of the Susquehanna River. Upon its completion, it is the second largest hydroelectric power plant in the United States. (Image courtesy Cyber Insket/Flickr)

- 1930s – The Great Depression spurs public works projects that repair and expand the region’s roads, bridges, parks and electrical services into rural areas, encouraging population growth. An interstate conference on the Chesapeake Bay recommends treating the Bay as a single resource unit rather than separate bodies of water. (Image courtesy Beaverton Historical Society/Flickr)

- 1940s – The “suburb” is born. People begin to use synthetic fertilizers on their lawns and fields, polluting local waterways. Maryland and Virginia create water pollution control agencies. The fishing industry increases its range and mobility, causing local fish populations to decline. Dermo, a disease that kills oysters, is discovered in the Chesapeake Bay. (Image courtesy Virginia Institute of Marine Science)

- 1950s – The 4.2-mile Chesapeake Bay Bridge is built, opening Maryland’s Eastern Shore to development. Across the region, developers drain and fill wetlands to build new houses, stores and office buildings. MSX, a disease that kills oysters, is found in the lower Chesapeake Bay. (Image courtesy Radio Rover/Flickr)

- 1967 – The Chesapeake Bay Foundation is formed. (Image courtesy David Clow/Flickr)

- 1963 – The 17.4-mile Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel opens, connecting Virginia Beach with Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Interstates 66, 70, 83, 95, 270, 495 and 695 are completed. The personal car has become the choice mode of transportation for Americans. (Image courtesy Barabara Rich/Flickr)

- 1800s – Oyster harvests increase dramatically. New England fishermen travel to the Chesapeake Bay with a device that scoops hundreds of thousands of oysters from their beds. Virginia and Maryland eventually ban this equipment. Maryland legislation states that only Maryland citizens can transport oysters in the state’s waters.

- 1910s – A District of Columbia law restricts the height of city buildings, causing development to expand outward. Baltimore installs separate wastewater and stormwater systems to filter water before it flows into the Chesapeake Bay. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act establishes hunting seasons and limits on international migratory waterfowl. (Image courtesy ghbrett/Flickr)

- 1960s – The 17.4-mile Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel opens, connecting Virginia Beach with Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Interstates 66, 70, 83, 95, 270, 495 and 695 are completed. The personal car has become the choice mode of transportation for Americans. (Image courtesy Barabara Rich/Flickr)

- 1970s – The region’s forest cover declines due to population growth and development. An increase in polluted runoff and damage from Hurricane Agnes destroy underwater grass beds in the Chesapeake Bay. Restoration partnerships like the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay and the Susquehanna River Basin Commission form.

- 1972 – The Clean Water Act is passed, establishing water quality standards and limiting the amount and kind of pollutants that can enter rivers, streams and other waterways. (Image courtesy Mr. T in DC/Flickr)

- 1973 – U.S. Senator Charles Mathias tours the Chesapeake Bay shoreline and sponsors legislation that prompts the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to conduct a study on the Bay’s health. This marks the first time that the Bay’s degrading health is brought to the public’s attention. The Endangered Species Act is passed, protecting endangered species and the ecosystems on which they depend. (Image courtesy Pulpolux/Flickr)

- 1980s – The Chesapeake Bay Commission, a tri-state legislative body that represents Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania, is established to coordinate policy across state lines. The Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay begins a first-of-its-kind program that teaches citizen volunteers how to monitor water quality.

- 1983 – The first Chesapeake Bay Agreement is signed by Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania; the District of Columbia; the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; and the Chesapeake Bay Commission. The Chesapeake Bay Program is established and the Chesapeake Executive Council is named the chief policy-making authority in the watershed.

- 1984 – Maryland passes the Critical Area Act to better manage continued growth. The law leads to the formation of the Maryland Nontidal Wetlands Protection Program, which works to conserve, create and monitor nontidal wetlands, slowing the loss of this critical ecosystem.

- 1985 – Six years after Congress passes the Emergency Striped Bass Act, Maryland imposes a moratorium on striped bass fishing. Virginia soon follows suit, in hopes that a closed fishery will help the species recover from harvest and pollution pressures. A Maryland ban on phosphate-containing laundry detergent reduces the amount of phosphorous flowing from wastewater treatment plants into the Chesapeake Bay

- 1987 – The 1987 Chesapeake Bay Agreement sets the first ever numeric goals to reduce pollution in the Chesapeake Bay, aiming to lower the nitrogen and phosphorous entering the Bay by 40 percent by the year 2000.

- 1988 – Virginia passes the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act, guiding local governments to address the environmental impacts of development and pushing communities to better manage urban and suburban growth. Maryland State Senator Bernie Fowler’s Patuxent River Wade-In establishes the “sneaker index” as a measure of Bay health, boosting public interest in water quality.

- 1989 – Maryland and Virginia lift the ban on striped bass fishing. The fish is declared a recovered species six years later.

- 1990s – The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Great Waters Program acknowledges that air pollution contributes to water pollution. The Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay begins to host week-long paddling trips down some of the watershed’s biggest rivers. The Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration begins selling “Treasure the Chesapeake” license plates, which support the Chesapeake Bay Trust. (Image courtesy Airliners.net)

- 1992 – Amendments are made to the 1987 Chesapeake Bay Agreement that aim to attack nutrients at their source: upstream tributaries that flow into the Chesapeake Bay. The Clean Vessel Act establishes a grant program to fund the construction of pumpout stations at marinas across the watershed, presenting a viable alternative to the overboard disposal of sewage. (Image courtesy spike55151/Flickr)

- 1993 – A law passed in Pennsylvania requires certain farmers to develop and implement nutrient management plans, limiting the amount of nitrogen and phosphorous that can run off of farms and into local waterways. In 1994, Virginia follows suit. In 1998, Maryland enacts similar legislation.

- 1994 – The Bay Program’s Riparian Forest Buffer Panel develops ground-breaking goals for the conservation and restoration of streamside forests. Federal and state incentive programs encourage landowners to install forest buffers on their properties.

- 1995 – The Local Government Partnership Initiative is signed to provide assistance to the 1,650 local governments in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. (Image courtesy adactio/Flickr)

- 1996 – Blue Plains Wastewater Treatment Plant begins to use nutrient removal technology to lower the amount of nitrogen it sends into the Potomac River and improve water quality. Federal, state and private partners agree to restore Poplar Island using sand and sediment dredged up from the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay.

- 1997 – The Virginia Water Quality Improvement Act establishes a state fund that will support the prevention, reduction and control of nutrient pollution. Maryland passes a package of legislation to combat suburban sprawl and direct smart growth. The initiative is praised as an innovative way to preserve natural resources and pursue sustainable development.

- 1998 – The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission closes Atlantic sturgeon fishing along the East Coast. The 40-year ban is the longest fishing moratorium on record. The Maryland Water Quality Improvement Act calls for the addition of a phosphorous-reducing enzyme to poultry feed, lowering nutrient levels in poultry litter. (Image courtesy Joachim S. Muller/Flickr)

- 1999 – The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation establishes the Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund to help communities restore polluted rivers and streams. The fund awards $8 to $12 million each year to on-the-ground conservation. The Virginia Land Conservation Act establishes a state tax credit to reward those who donate land or easements for conservation.

- 2000 – Maryland records its lowest blue crab harvest: 20.2 million pounds. Chesapeake 2000 is signed, establishing more than 100 goals to reduce pollution and restore habitats, protect living resources and promote sound land use, and engage the public in restoration. The National Park Service and its partners launch the Chesapeake Bay Gateways and Water Trails Network to connect people with the Bay’s places and stories. (Image courtesy Brian Talbot/Flickr)

- 2002 – More than 2,800 miles of forest buffers have been restored in the watershed, meeting the Bay Program’s goal for forest buffer restoration eight years ahead of schedule. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration establishes the Bay Watershed Education and Training program to fund the delivery of Meaningful Watershed Educational Experiences and advance environmental education in the region.

- 2003 – The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issues water quality criteria for the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries. Representatives from the Bay’s headwater states join the Chesapeake Executive Council. The Chesapeake Bay Watershed Blue Ribbon Panel is created to find new financing opportunities for restoration work, and the Chesapeake Bay Funders Network is established to bring grantmakers together.

- 2005 – The Chesapeake Executive Council adopts an animal manure management strategy to reduce nutrient pollution from livestock operations.

- 2006 – The Chesapeake Executive Council adopts new directives to expand forest cover, reduce the amount of phosphorous in lawn fertilizers and increase funding for on-farm conservation programs. The Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail is designated. The Living Shorelines Summit furthers research on the use of living shorelines to control erosion. (Image courtesy Jane Thomas/IAN Image Library)

- 2007 – The Chesapeake Executive Council signs the Forest Conservation Initiative, committing to conserve 695,000 acres of forests by 2020. The Chesapeake Bay Interpretive Buoy System (CBIBS) is launched to report real-time environmental data. BayStat is launched to track restoration progress. The Bay blue crab harvest of 44.2 million pounds is one of the lowest recorded since 1945.

- 2008 – Maryland, Virginia and the Potomac River Fisheries Commission issue emergency regulations on the harvest of blue crabs to help the species recover. The Chesapeake Bay’s blue crab fishery is declared a federal disaster. The 2008 Farm Bill dedicates more than $180 million over the course of four years to agricultural conservation. The invasive zebra mussel is found in the Maryland portion of the Susquehanna River.

- 2009 – President Obama signs an executive order that calls on the federal government to renew the effort to protect and restore the watershed. The Chesapeake Executive Council sets two-year milestones to accelerate restoration and increase accountability. Annapolis becomes the first jurisdiction in the watershed to ban phosphorous in lawn fertilizer.

- 2010 – Maryland, Virginia and New York ban phosphates in dishwasher detergent to lower phosphorous pollution in local waterways. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency establishes the Total Maximum Daily Load to limit the amount of pollutants that can enter the Chesapeake Bay. The Bay Program launches ChesapeakeStat to improve communication about restoration goals, progress and funding. (Image courtesy Lydiat/Flickr)

- 2011 – The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issues a new Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Permit to the District of Columbia. It is the first of its kind to incorporate green infrastructure into its requirements, setting a national model for stormwater management.

- 2012 – Harris Creek becomes the first target of the oyster restoration goals set forth in the Chesapeake Bay Executive Order: to restore oyster populations in 20 Bay tributaries by 2025. In this Choptank River tributary, existing reefs will be studied, new bars will be built and spat-on-shell will be planted.

- 2013 – A federal judge rules that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency can set pollution limits for the Chesapeake Bay, thus upholding the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) that was challenged in court in 2011. (Image courtesy cplong11/Flickr)

- 2014 – The Chesapeake Executive Council signs the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, which contains goals and outcomes that will guide conservation and restoration across the watershed. For the first time, the Bay’s headwater states commit to those goals that reach beyond water quality.

Ms. Dickinson, thanks so much for all the information on here! I am currently doing some research on the Native American Indians located in the Chesapeake Beach, MD area. Was wondering if you had any information on what tribes were located in that area? I know Capt. John Smith landed there with his crew during his exploration’s of the Chesapeake (1607-1609) for 1 night. I know there were also 2 sites in that area were the Indians had camps (one was at the mouth of Fishing Creek and has since eroded away over time). Any info. you could provide would be very helpful. Thanks, Scott Nieman

LikeLike

I was running out yesterday when I responded to your comments. This morning I looked at the Calvert Historical Society sites. Here’s the link to the page that talks about Captain John Smith and the Indians of Calvert County: http://calvert.lib.md.us/history/calvfrontcb_09.jpg

LikeLike

Hi there! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a collection of volunteers and starting a new

project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us valuable information to work on. You have done a marvellous job!

LikeLike

Hayley–thanks for your comments. Would enjoy learning more about your project.

LikeLike

Pingback: Our Native American Heritage–A Follow On | Our Heritage: 12th Century & Beyond